Learning From Worm Infections

Approximately 1.5 billion people around the world are infected with parasitic worms. However, these infections are the subject of comparatively little research such that many of them are now classified within the group of so-called neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) that are strongly associated with poverty.

Asian tiger mosquitos normally live in southern tropical areas. However, due to climate change and human migration, they are travelling to new areas and becoming a bigger global health issue. The problem is that these unwanted intruders can transmit pathogenic worms and viruses to humans. The spread of an insect therefore demonstrates that diseases, and their carriers, do not stop at national borders if the conditions suit them.

Professor Clarissa Prazeres da Costa, a physician at the Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene (MIH) at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), has been exploring parasitic worms for years. These worms enter the human body through mosquito bites, in food or drinking water contaminated with urine and feces, or they burrow directly through the skin. Until about a 100 years ago, worm infections were widespread in economically developed countries. Yet they have been virtually unheard of in Germany in recent times. However, the situation is changing.

"Problems we now face in tropical or subtropical areas already affect us in central Europe and will do so even more in future. Therefore, our ways of thinking and our research about the etiology, development and causes of diseases must become much more global," says Prazeres da Costa.

Worm Infections Weaken the Immune System

These diseases are the subject of comparatively little research. But the small parasites, known as helminths in technical language, can even teach scientists lessons. They have developed with the human immune system for a long time. "As immunologists, we can learn a lot from our ‘old companions’ by better understanding how they manage to trick our immune system. This knowledge also enables us to find novel drugs and therapies to fight them," says Prazeres da Costa, who heads the research group “Infection and Immunity in Global Health” at the MIH.

Almost every organ in the human body can be occupied by these worms, with each parasite gradually carving out its own niche, from the skin and the liver to the brain. Symptoms of infection can range from mild digestive problems or anemia to severe growth and development disorders in children.

In order to survive in their host for as long as possible, worms need to outsmart the human immune system—and precisely how they achieve this is a fascinating process that Prazeres da Costa wants to understand better. She and her team have discovered, for instance, that helminths release molecules that actively inhibit the body’s innate immune response. In addition, the worms induce increased release of suppressor cells, which further suppresses active responses from the immune system. This "immunomodulation" also influences how people infected with helminths react to other conditions such as allergies, other infections like hepatitis B and C, and even vaccinations, namely by weakening the body’s response in many cases.

Developing a Global Network to Address Global Health Problems

In addition to investigations in animal models of disease, the research team runs different studies in sub-Saharan countries such as Gabon to examine how parasitic infections influence pregnancy, the immune system of the offspring, and women’s health in general. Two new branches of her group have just started to explore how novel technologies can support diagnostics and treatment of NTDs. To drive this research forward, Prazeres da Costa founded the Center for Global Health (CGH) together with her colleague Andrea Winkler from the Department of Neurology in 2017. At this center, interdisciplinary scientific and educational projects on global health are initiated or otherwise supported and connected with each other.

TUM and Ghana—an International Partnership

The Center for Global Health at TUM School of Medicine actively supports TUM’s engagement with the African continent. At the heart of this commitment is a strategic university partnership with Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Ghana.

After successfully collaborating for many years, TUM and KNUST entered into an institutional partnership for innovation and sustainable development in 2018. This has led to clinical collaboration and the exchange of medical knowledge as well as clinical staff.

The two universities also work closely together in future-oriented areas such as water and energy research, environment, mobility and global health, and entrepreneurship.

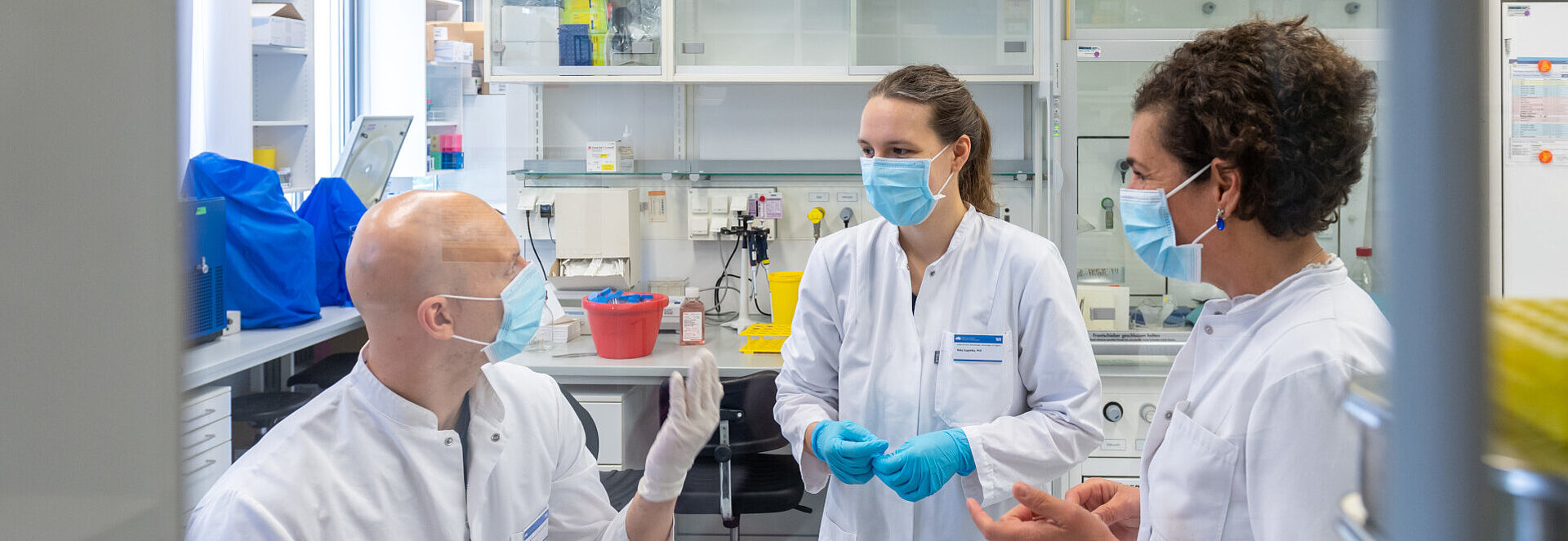

Young Academics for a Healthier World

For Prazeres da Costa, who herself has Indian roots, it is important to sensitize young academics to the main problems of global health and to win them over for her research. Postdoctoral and doctoral candidates from seven different nations work in Prazeres da Costa’s lab. Apart from their lab work and lectures and workshops for students from different disciplines, Prazeres da Costa’s team also participates in the TUM Global Week every year, which is a platform event that brings together people from all over the university as well as external partners and alumni to exchange ideas on internationalization and international experience.

"We feel strongly obligated to pursue the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly the third goal of ‘ensuring healthy lives for all’," Prazeres da Costa says. She contributes to this mission through her research, including that into helminths, and through her commitment to promoting interdisciplinary research at the CGH together with her colleagues from all over the world.