Is Artificial Intelligence Intelligent?

Artificial intelligence (AI) presents a vast array of possibilities. Beginning in 2021, the Bavarian state government plans to establish seven new AI-focused professorships at the University of Bamberg. In this interview, three Bamberg researchers, computer scientist and psychologist Ute Schmid, philosopher Christian Illies, and computer scientist Diedrich Wolter, discuss just how intelligent AI is, and how AI research can benefit from interdisciplinary collaboration. The guest of honor is the voice recognition software Siri.

Siri, how are you feeling?

Siri: Everything’s groovy.

Say something.

Siri: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

How does Siri work?

Wolter: As far as this example is concerned, a few typical questions and some corresponding answers have been formulated that could be asked to a system like Siri, which then selects an answer at random. This is a simple example. There is no intelligence involved beyond the recognition of spoken language.

Schmid: Siri’s response behavior is based on pattern recognition, but Siri can also respond a bit more flexibly. Instead of linking a fixed question to a fixed answer, Siri can also deconstruct simple sentence patterns and respond sensibly to a whole group of queries.

Wolter: Essentially, Siri is a representative of the question answering systems that are composed of various AI components. Besides giving amusing answers, she can answer questions like “What's the weather going to be like today?” By means of programming, the system bases its answer on the location of the person asking the question. To find the precise answer, Siri will, for example, use a search engine.

Siri, are you intelligent?

Siri: I have a great deal of knowledge at my disposal. And I look for ever more intelligent ways to use it.

Schmid: Well, our fellow computer scientists have in fact programmed a good answer to this question ...

Illies: Although, strictly philosophically speaking, one would say the definition here is circular. When Siri answers the question about her intelligence by saying that she is looking for more intelligent means, she is presupposing that she is intelligent, but she has not really identified in which way she is intelligent.

Wolter: I would argue based on fixed-point semantics that the definition holds. You define the term by itself, and the whole thing can mathematically result in a well-defined fixed point. So yes, I could live with Siri’s definition.

Illies: The question is what the well-defined fixed point would be in this case. And, in pragmatic terms, we can of course live with the fact that the computer is in a bad mood, is intelligent, or suchlike.

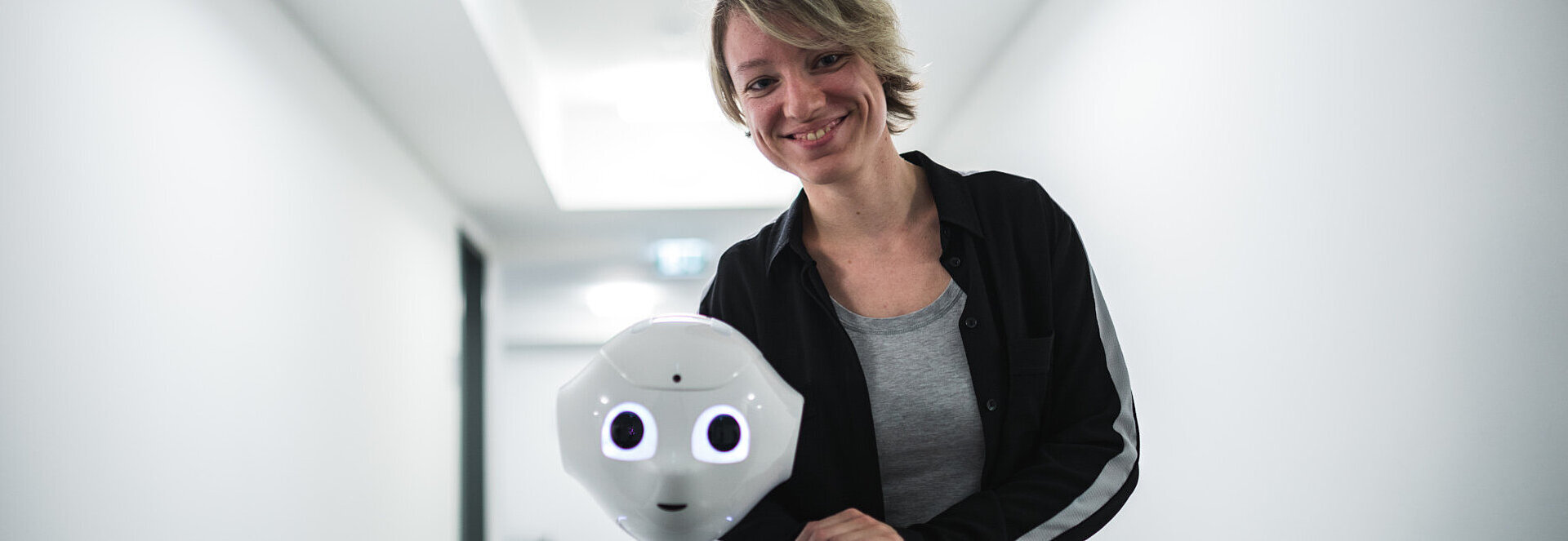

Schmid: Speaking as a psychologist, when we ascribe intelligence or feelings to a system, it is based on our need to ascribe intentionality to a counterpart. If you stroke Pepper the robot’s head, he says, “Oh, I'm ticklish!” and you can almost believe it. But this reaction is just as pre-programmed as any of Siri’s.

Seven new KI-Professorships/Chairs

The focus on Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being greatly expanded at the University of Bamberg. Seven new professorships have been established as part of the technology offensive known as Hightech Agenda Bayern. The professorships cover the following areas of research:

- AI Systems Engineering

- Multimodal Intelligent Interaction

- Explainable Machine Learning

- Natural Language Generation and Dialogue Systems

- Fundamentals of Natural Language Processing

- Computational Social Science and AI

- Information Systems, especially AI Engineering in Companies

What distinguishes AI from humans?

Schmid: When we speak about human intelligence, we usually mean general intelligence. If someone is very good at maths, we assume that they can also understand jokes. Typical AI systems can’t do this. A deep neural network that reliably recognizes traffic signs cannot identify animal species or tell jokes. Artificial intelligence is usually restricted to a very narrow field.

Illies: That is certainly a decisive criterion, but the question is whether we aren’t already assuming that consciousness is an integral part of intelligence. Machine intelligence primarily comprises a complex processing capability, which, to some extent, we also find in Siri and AI. In this respect, humans are similar. Somewhat like a human being, the computer interprets a sensory impression as a face. The difference is that with human intelligence perception is an act of consciousness. Machines are intelligently programmed, but they are not conscious in the same way that humans are.

What is the essence of being human?

Illies: That is an infinitely large question. Consciousness is undoubtedly a central aspect of being human, especially self-reflection—that is, the capacity for self-awareness. We would not attribute that to a computer. According to all that we assume, computers remain complex cigarette machines. Being human involves experiential qualities, above all the ability to love and cherish, or to experience things subjectively. Identifying the color red is altogether different from experiencing red. And then there's consciousness and our awareness of our own mortality. Understanding oneself also means recognizing one’s own finiteness. All this is completely beyond AI.

Schmid: Not long after the birth of AI in 1956, philosophers were already exploring the limits of AI systems. However, some of the aspects discussed at that time were rendered irrelevant by the continuing advancement of AI approaches. But I absolutely agree that the big questions—regarding consciousness, for instance—can only be addressed collectively with other disciplines, especially philosophy.

Illies: AI has undergone an exciting evolution since its beginnings. And we don’t know where it’s headed. At the moment, we don't even know how we will ever be able to determine whether it has consciousness. How are we supposed to know whether a computer that answers all questions as perfectly as a conscious being actually possesses consciousness?

Schmid: I also believe that human beings cannot completely comprehend themselves. Maybe we can understand a housefly or a rat, but I personally consider it impossible for a human being to understand another human being in their entirety.

Illies: The problem of other minds: How do I know that you …

Schmid: ... that I’m not a zombie or an AI. Exactly, you don’t know. (laughs)

Illies: There are good indications that you are a human, but that’s only an approximation that I make by projecting my self-awareness onto you. The inverse reflections are also very intriguing. AI research is helping philosophy to reframe its own questions.

AI research is becoming increasingly important. Seven new, interdisciplinary professorships are being created at the University of Bamberg. In which areas will they conduct their research?

Wolter: On the one hand, we want to continue to expand the field of reliable, reproducible AI research. On the other hand, we want to further develop AI to process additional types of data and information, such as in the area of text comprehension.

Schmid: We specifically chose focus areas for the AI professorships that form bridges to research topics in the other three faculties. That way the various disciplines can collaborate and cross-pollinate. Language processing is a good example. The topic can be approached algorithmically and technically from an AI perspective, or it can be approached linguistically and philologically.

Illies:It’s fascinating to me how AI offers us new forms of meta-research that are relevant to all faculties. AI is a specialized field, but at the same time, its breadth of application means it has a place in almost every subject.

Schmid: Our founding dean, Elmar Sinz, was very farsighted in organizing applied computer science in the same way from the start. The entire applied computer science professorial staff has been appointed in such a way that we are all open to interdisciplinary cooperation.

Centre for Innovative Applications of Computer Science (ZIAI)

Members of all faculties at the University of Bamberg are involved in contributing to research in the “Digital Humanities, Social and Human Sciences.” The goal is to develop innovative information technologies and digital solutions through collaborative research.

The Centre for Innovative Applications of Computer Science (ZIAI) provides an organizational framework for collaborative research, promoting interdisciplinary exchange both within the university and with national and international research institutions. ZIAI focuses on application problems that arise in the humanities and the social and behavioral sciences. As a service to members of the University of Bamberg, ZIAI also provides scientific support to a selected number of research projects.

ZIAI involves researchers—including PhD candidates and postdocs—who contribute to four major areas of study:

- Digital Heritage

- Digital Teaching and Learning

- Cognition and Interaction

- Sociotechnical Systems

How exactly do Bamberg's philosophy and computer science departments work together?

Schmid: Prof. Illies, a postdoctoral researcher, and I are currently planning a joint research project on problems of concept formation. We want to employ methods from both philosophy and AI to explore how people acquire concepts through induction, that is, from experience.

Illies: Additionally, Prof. Schmid and I want to offer a seminar together. Prof. Wolter, we'll get something going too!

Wolter: I'm definitely open to that. There are already enough points of contact.

Illies: Philosophy is always an attempt to conceptualize one’s own time, as the German philosopher Hegel says. Philosophy only works if it reflects the empirical knowledge and technical abilities of its time. That's why we also have to reflect philosophically on AI.

Schmid: I think that we can work together not only on such epistemological questions but also in the field of ethics. It may not make sense for a robot to read aloud in an elderly care home because human interaction is vital in that setting. But it does make sense for a robot to assist with heavy lifting. AI can’t and shouldn’t solve this on its own; the socio-technical context also has to be taken into account. What kind of world do we want to live in? Diedrich Wolter and I advocate for AI that expands and promotes people’s competences instead of constraining people within their competences.

Wolter: There’s also the question of whether AI is dangerous. For the moment, AI is just a method we use to make tools. Every tool can become a dangerous object. Cars too. It is a question of decisions and design: Where do we want to go as a society? The answer won’t be decided in research labs but by the broader society. The task of the university is to educate citizens so that they can make an informed decision.

Illies: I think it is significant that you both emphasize this question: What kind of world do we want? Let’s take online shopping behavior as an example. In many cases, people seem to want a world in which they pay for the enjoyment of shopping while being subject to intrusive data collection methods and manipulation. That's why we have to add a question: Do we want people to want a certain world? We should also ask this question with regard to AI.

Thank you very much for the interview!

Siri: It was my pleasure!